Through 85 paintings, all but one of which passed through Durand-Ruel’s hands, it tells the story of the triumph of impressionism. Durand-Ruel’s achievement as cheerleader, entrepreneur, patron, and helpmeet is the subject of the National Gallery’s new exhibition Inventing Impressionism: The Man who Sold a Thousand Monets. To gain them the recognition he was convinced they deserved, he developed a range of new ways of promoting them that redefined the relationship between dealers and artists. It was a long-term project born of his faith that financial rewards – for the artists as much as himself – would come when the rest of the world saw them the way he did. Innovative artists needed an innovative dealer and Durand-Ruel’s particular genius was not just to spot the talent of the young impressionists, but to promote them indefatigably and create a market for them where previously there had been none. Photograph (Musée d’Orsay) /Hervé Lewandowski. To think that, had I passed away at 60, I would have died debt-ridden and bankrupt, surrounded by a wealth of underrated treasures.” As he noted: “My madness had been wisdom. For Durand-Ruel, it was validation of his steadfast support for this group of avant-garde painters which had several times put him on the point of financial ruin. For Monet, Renoir, Pissarro, Sisley and their peers it was final confirmation that their struggle to win acceptance for their unacademic, light-infused paintings had been successful.

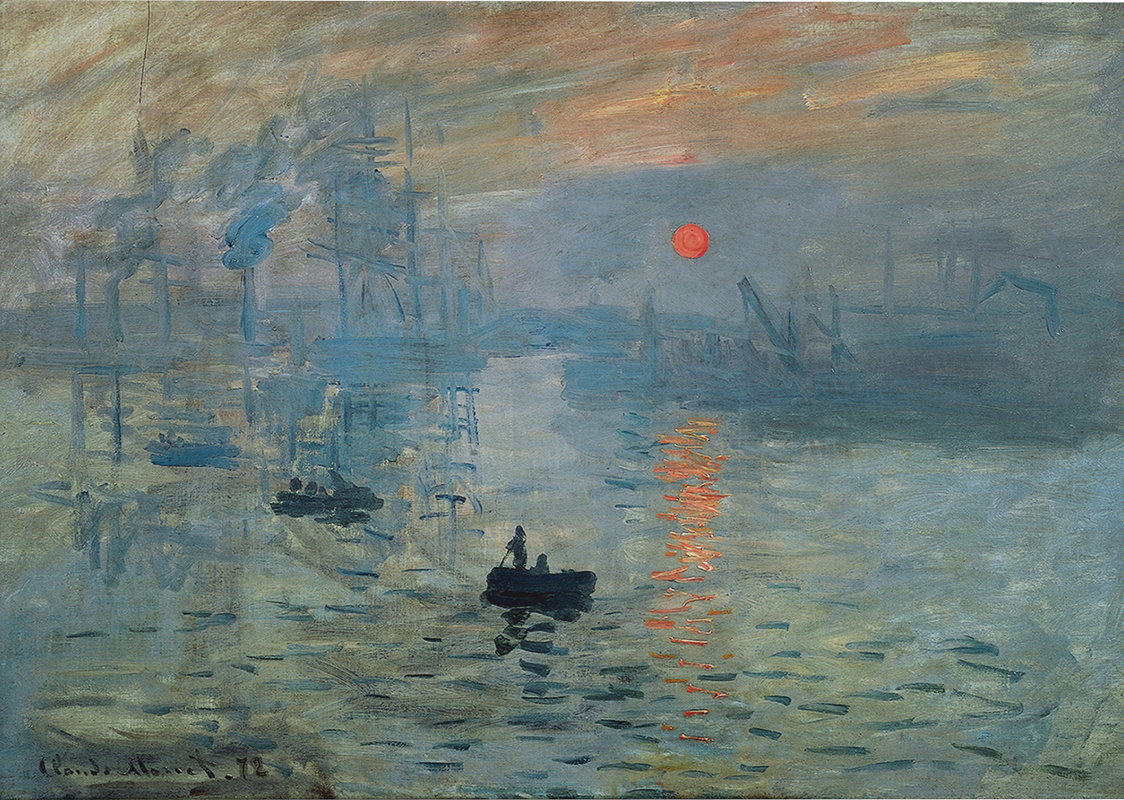

The exhibition, sometimes known as The Apotheosis of Impressionism, contained 315 pictures and was, and remains, the largest show of impressionist works ever held. This meeting and the chain of introductions, friendships and innumerable business transactions it put in motion was to culminate 24 years later with an exhibition just down the road on Bond Street at the Grafton Galleries. Whether or not the gallerist believed Daubigny’s words of introduction – “This artist will surpass us all” – he liked Monet’s work well enough to buy numerous canvases and, a few days later, paintings by his fellow artist-refugee Camille Pissarro, too. It was in January that year that the landscapist Charles-François Daubigny took him along to the inaptly named German Gallery on New Bond Street and introduced him to the proprietor, another French expat, named Paul Durand-Ruel (1831-1922). In 1871, having fled the Franco-Prussian war, Claude Monet was living in London. It is another irony that the key figure in the movement was not a painter but, that most maligned of species, a dealer.

It is one of the ironies of impressionism, the quintessential French movement, that it had its beginning and its end not in Paris but in London.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)